“Ata Ndele”: sooner or later, independence will come

#CongoFreedom (episode 2) by Vladimir Cagnolari

In our last episode, PAM visited a post-war Congo-Leopoldville (currently DRC), at a time when new sounds and ideas began to form. These would, in time, lead the country to independence, on June 30th, 1960. Naturally, music played a key role.

Adou Elenga’s song “Ata Ndele” (“sooner or later”) was released in 1956. It foreshadowed, although implicitly, the impatience of the Congolese people which would lead to them eventually taking control of their own history. That same year, a young Patrice Lumumba arrived in Léopoldville, currently Kinshasa. Two years earlier, he had obtained a registration card whilst working at a post office in the northeast of the country. This precious document entitled him – as well as a handful of other Congolese – to new civil rights closer aligned to that of the Belgians. Upon his arrival in the capital, he was hired as commercial director for the Polar brewery. A gifted speaker, he drew comparisons in the virtues of beer and freedom, both something that people were thirsty for. The renowned Antilles-born poet and dramatist Aimé Césaire staged this very character in his play Une saison au Congo (“A Season in the Congo”), published in 1966.

“My children, the whites invented many things and what they brought to you here is both good and bad. On the bad side of things, I won’t say much today. But what is quite sure, quite certain is that among the good, there is beer! Drink up! Come on! Besides, isn’t that the only freedom they are giving us? We can’t gather together without ending up in prison. Meet: prison! Write: prison! Leave the country: prison! And anything else for that matters…But see for yourself: I have been ranting at you for a quarter of an hour and the cops allow me to do so… I travel the country from Stanleyville to Katanga, and their cops let me do so! Why? Because I sell and promote beer! So we can definitely now say that the beer glass has become a symbol of our Congolese rights and freedoms! […]

Polar, the freshness of the poles in the tropics! Polar, the beer of Congolese freedom! Polar, the beer of friendship and Congolese society!”

Lumumba quickly established himself as a public speaker, and artists like Vicky Longomba began to sing about him and his movement, the MNC – Mouvement National Congolais (“Congolese National Movement”).

Lumumba founded the MNC party at the end of 1958, choosing the name as a program in itself: it promoted a “national” movement, whereas other political parties were regional associations of people – such as Abako, which brought together the Bakongo, a people from the South, where the capital Leopoldville was built.

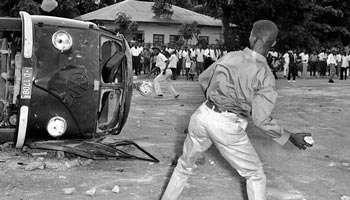

But enough of those alcoholic ramblings: history isn’t only discovered in the bottom of a beer cup. What we know for sure, is that on January 4th 1959, a meeting of the Abako, the other major party, was prohibited in Leopoldville. Clashes with the police eventually descended into riots: the city declared being under siege, and 47 Congolese were killed (according to Belgian data, clearly lower than the true figures).

In Brussels, colonial authorities began to discuss independence, hoping it would diffuse the conflict. But soon after, in the North, supporters of Lumumba were chased down too… As for the leader of the MNC, he was firstly thrown in jail, before being released – under pressure from the Congolese delegates – and then put on a plane for Brussels. This is where the Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference would take place: discussions that brought together the Belgian authorities and representatives of Congolese political parties over the course of a monthto discuss independence, its conditions, and its calendar.

The Congolese delegation brought along with it one of the great orchestras of the time: Joseph Kabasele’s African Jazz. It’s January 1960, and he sings about the round table in the song “Table Ronde”.

In Brussels where the Round Table Conference was taking place, a young Cameroon-born man who grew up in France, arrived a few months earlier. His name was Emmanuel N’Djoké Dibango: that’s right, the Great Manu Dibango. He was meant to resume his studies in the Belgian capital, but he chose rather to spend his time playing sax in the club ‘Les Anges Noirs’. This is also where Congolese delegates met every evening in order to relax, while continuing their discussions on strategy for the negotiations.

At the Round Table Conference, a date for the independence of Congo was eventually decided on. It would be on June 30th, that same year – in just five months’ time. In May, legislative elections gave victory to Lumumba’s MNC but, without a sufficient majority, they had to form a coalition government, which resulted in a lot of compromising. Three-quarters of the party’s members were under 35 and the youngest, at just 26, was the first Congolese to have graduated from university. Finally, the long-awaited day had come.

In Léopoldville, King Baudouin of Belgium gave a speech on the great work accomplished by his predecessors in the Congo. He was succeeded by Kasavubu, the leader of the Abako party who was appointed president. The latter gave a very polite, cursory and unified speech. Then it was Lumumba’s turn to speak.

Of course, Lumumba’s speech came to upset the Belgians pretty badly. But outside, in the streets, in the ngandas (restaurants) and the bars, people were singing and dancing the Indépendance Cha-Cha.